Value – the importance or significance of something; an abstract noun corresponding to the verb value. In Latin, Valere, carried over into some languages with a similar connotation (French: valeur, English: value, Italian: valore – price, value, significance, etc.), originally meant strength and health, as well as feeling healthy. This original meaning of the word has been retained in many derivative words. It has also been extended to describe the strength of mind and dignity, which many peoples have designated with the same word to express bodily strength. Furthermore, as psychotherapists, we can draw a parallel with self-value as the basis of one’s psychological health, one’s sense of being present in the world and one’s inner strength, which many of the participants in the study underlying this article spoke about.

Abstract

The article is based on a phenomenological study of self-worth at the Baltic Institute of Psychotherapy in 2022. Although self-worth is one of the most crucial concepts of humanistic psychology and psychotherapy, very few theoretical and empirical works are devoted to its study to date. Moreover, there is considerable ambiguity surrounding related ideas, particularly self-esteem. One of the few authors who writes about self-worth as a separate phenomenon is Prof. Alfried Längle. His ideas served as the foundation for the study and this article, illuminating “self-worth” from several perspectives: cognitive, affective and behavioural manifestations, features of understanding self-worth by adults through metaphorical images and a resource of self-worth as a phenomenon for psychotherapy. The conducted factor analysis made it possible to reveal the structure of the phenomenon and describe it through specific categories, consistent with the humanistic tradition of understanding human psychology.

Keywords: self-worth, self-esteem, psychotherapy, research in psychotherapy, phenomenological analysis

Sometimes one has to peer into something to understand its value…

Value – the importance or significance of something; an abstract noun corresponding to the verb value. In Latin, Valere, carried over into some languages with a similar connotation (French: valeur, English: value, Italian: valore – price, value, significance, etc.), originally meant strength and health, as well as feeling healthy. This original meaning of the word has been retained in many derivative words. It has also been extended to describe the strength of mind and dignity, which many peoples have designated with the same word to express bodily strength. Furthermore, as psychotherapists, we can draw a parallel with self-value as the basis of one’s psychological health, one’s sense of being present in the world and one’s inner strength, which many of the participants in the study underlying this article spoke about.

Am I valuable?

What is my value as a person?

Why is it so rare to truly appreciate myself as I am without additions and improvements?

The inquiry of self-worth is one of the most pressing issues raised in a psychologist’s or psychotherapist’s room. However, it is most often formulated through related concepts: self-esteem, self-respect and self-confidence, as well as a variety of manifestations such as the inability to build personal boundaries and take care of oneself, lack of responsibility, inability to create respectful and trusting relationships with others (which, as we know, are never better than relationships with oneself), feelings of insignificance and needlessness.

A substantial part of the queries to work with a psychologist/psychotherapist are formulated as follows: I struggle with low self-esteem, I do not feel that I am worth something, that my life is worth something, I do not feel needed, I feel that I do not deserve love or respect, I cannot accept myself… In all these queries, we hear the problem of self-value. At the popular psychology level, the “express answers” to these queries are often in the vein of advice to improve self-esteem, to love, accept and appreciate oneself unconditionally. In essence, something very close to the message of the famous commercial: “Stop it!”. However, what is the therapeutic strategy for dealing with a person’s self-worth, and what is this phenomenon? We will try to address these questions in this paper.

A sense of self-worth is pivotal, depicting a person’s underlying relationship to himself or herself. As psychologists and psychotherapists, we know to what extent self-perception determines one’s sense of self in the world and one’s relationship with the world and others in it.

The concept of self-relatedness started to evolve at the end of the 19th century, with the publication in 1890 of the seminal work of the American psychologist and philosopher William James, The Principles of Psychology. According to James (1890), a person’s sense of self-worth depends entirely on their goals in the world and, therefore, on their achievements in the realms of values. More than a century later, this idea forms the basis of one of the modern CSW models of self-worth (the contingencies of self-worth, Crocker, Wolfe 2001). Initially based on intuition rather than on validated knowledge, the authors proposed the idea of conditioning self-worth on contingencies, arguing that there are areas in which success or achievement enhances self-worth. At the same time, failure and setbacks compromise one’s sense of self-worth (Crocker et al 2003). Within this model, an understanding of self-worth is virtually identical to that of self-esteem, including terminologically, the authors use the two words as synonyms, which is clearly presented, for example, in a descriptive, theoretical paper on the topic of the search for self-worth (in the original English version, the paper is entitled “The Insatiable Quest for Self-Worth”, Crocker, Nuer 2003). We will discuss the CSW model and the measurement methodology based on it later.

Meanwhile, it is worth noting that William James’ ideas, in general, are a kind of point of reference for scientific research in this area, which had its most remarkable rise in the 1960s and 1970s and is reflected in the works of authors such as M. Rosenberg, S. Coopersmith, R. Wiley, R. Burns. These authors created new concepts and proposed research methods related to self-attitude, the core of personality, the emotional and evaluative attitude to the Self and other components of the Self. In psychotherapy, the worth of a person’s Self is revealed in the humanistic approaches and is represented in the works of C. Rogers, A. Maslow, E. Fromm. R. May, A. Längle and others.

“Related” concepts of self-worth can be a self-evaluation or “global self-esteem” (a term coined by Marshall Rosenberg), self-respect, and a sense of personal significance. As in the CSW model, self-esteem and self-worth are often used as synonyms. However, within the scope of this study, we distinguish these concepts, seeing a significant difference between them, which we will demonstrate sequentially.

Unlike self-esteem—a concept often confused with others in everyday life and literature—self-worth is not discerned through comparisons or the assessment of personal achievements. Instead, it is a stable phenomenon that manifests as a cognitive conviction, knowledge, and a feeling that ‘I’, as an individual and human being, have inherent value.

While self-esteem tends to be associated with a particular quality—such as physical appearance, professional success, financial well-being, or popularity in a reference group—self-worth is unconditional: ‘I’ am valuable in and of myself, independent of my achievements.

In the context of this substantive distinction, one could refer to the thesis of Erich Fromm: To Have or to Be (Fromm, 2022), where self-esteem is mainly dependent on what an individual possesses, while self-worth is predicated on who they indeed are.

Psychologist Christine Hibbert (Hibbert, 2022 )1 describes the state of self-worth as a feeling of “I am greater than all of those things”. It is the underlying knowledge that I am valuable that I can be loved that the world needs me. In this understanding, self-worth is related to self-esteem, but not as one aspect of it, but rather as a cause, a foundation on which one’s self-perception is further built. It is self-worth that enables one to feel ‘OK’ as a person who is generally ‘fine’ despite possible weaknesses, mistakes or limitations. Following many of our colleagues (including the above-mentioned Christine Hibbert), we are convinced that high self-esteem cannot be consistent without a sense of self-worth. Experiencing success can only be accompanied for a short time by a sense of contentment in oneself, and an increase in worth in the self, but in the absence of self-worth, the feeling of fulfilment quickly fades away, leaving a feeling of emptiness and a sense of imposture. One may devalue one’s own contribution to the outcome, seeing success as a one-off event. We see this phenomenon vividly in narcissism, which psychologist and psychotherapist Irina Mlodik (2017) describes, including through attitudes towards one’s own achievements: “The narcissist is basically in two polar states. He is either divinely beautiful and omnipotent (in moments of recognition of his achievements), or he is a complete failure and nothingness (in moments of his failures or non-recognition). Precisely so. The polarities are not “good-bad”, but namely “divinely awesome-totally worthless”. Furthermore, that is why he can easily and unnoticeably find himself in any of these states for himself and those around him. There is always one “toggle switch” for switching modes: an external or internal evaluation, connected in one way or another with external recognition or self-recognition <…> victory, triumph, achievement, receiving recognition. In these moments, the narcissist realises that he is not just ‘entitled to live’ but omnipotent, notably clever, beautiful, insightful, and has created something that will now make him feel good but great for the rest of his life. The joy is intense but short-lived, from a few minutes to weeks. Then there is a shattering collapse and again a succumbing void within.”

Forming self-worth as an essential personality quality is one of the most critical tasks of development and psychological/psychotherapeutic work. In fact, it is the basis that sets the nature of the behaviour, the way of building relationships with oneself and others, and unfolding various emotional experiences.

Stanley Coopersmith (1967) defines self-esteem as an individual’s gradual, habitual attitude towards oneself, manifesting as approval or disapproval. Through self-esteem, a person is assured of his or her worth and value. The author distinguished between two components of self-esteem:

1) self-evaluative component;

2) affective feeling component.

Coopersmith saw the basis of self-esteem in the following aspects: 1) power (influence/control of others); 2) significance (value to others/acceptance by others); 3) virtue (adherence to moral standards); 4) competence, or success in achieving goals (Coopersmith, 1967).

On her part, psychologist Ruth Wiley believes that self-esteem is a complex concept that rests on two pillars:

1) a person’s evaluation of himself;

2) the evaluation of a given person by those around him or her (Wylie, 1974; 1979).

This approach does not contradict the previous one but simply takes a different frame of reference. In addition, referring to Wylie’s model, we can surmise how self-esteem and self-worth are related, namely, that self-worth is part of a person’s self-esteem, which depends on the individual’s attitude towards himself or herself.

Christopher Mruk (1999), who has also researched self-esteem, notes that contemporary society often uses the term ‘self-esteem’, but no one can provide a precise and comprehensive definition of the term – as many researchers there are, there are as many different definitions. This observation may be even more applicable to the concept of self-worth.

As we pointed out above, within the framework of the psychotherapeutic approach, the issue of self-worth receives much attention from representatives of the humanistic approach. In particular, Carl Rogers, the founder of person-centred therapy, draws attention to the importance of an autonomous value process (cited in Orlov, 2002: 147), characterised by the fact that the individual freely manifests himself by being guided by his inner state and proceeds from inner values. This free behaviour based on natural needs is initially characteristic of all infants. However, according to Rogers, the autonomous value process is gradually disrupted by the effective value of the love of others (especially parents). In order to retain their love, the child realigns its behaviour according to the values of adults and eventually internalises these values, which take shape as a fixed system. As a result, the localisation of the value process becomes externalised, and the individual acquires a basal distrust of his own experiences and valuations, of his individual experience as the most important determinant of behaviour. Thus, according to Rogers, a fundamental disintegration of their self characterises typical members of contemporary culture, their conscious value systems and their unconscious value processes. This constitutes, at the same time, the main problem of psychotherapy.

Carl Rogers creates a kind of new psychotherapeutic myth, transforming the psychological model of the human being in the direction of absolute trust in the patient, the client, and the person. Setting up a fundamental theoretical distinction between two modes of existence, two forms of determining human behaviour – “value process” and “value system”, Rogers (1964) explains the entire field of psychopathology from neurosis-like states to psychoses as a consequence of not accepting and displacing adult existence in the logic of “value process” – free from any fixations, dynamic and open to the experience of personal growth. In this context, healing is seen as the main problem and task of psychotherapy, as the acquisition by the individual through acceptance and self-acceptance of their lost wholeness and the unconditional value of the self.

Alfried Längle, a psychologist and psychotherapist who develops logotherapy and existential analysis, pays considerable attention to worth in his work. In his book “Person, existential-analytical Theory of Personality” (2005), he presents the topic of self-worth (already in its pure form, without mentioning self-esteem) in great detail. Self-establishment and the formation of self-worth concerning the outside world is a vast theme that, according to Längle, accompanies every individual throughout his or her life. Who among us has not faced questions such as: Can I be who I am? Am I accepted as I am? Do I have the right to be myself – in my profession, partnership, and relationship with my parents? Moreover, in dealing with these kinds of questions, the society in which a person is/ develops plays an important role. In order to understand what I am allowed and what I am not, it is essential not only to feel my own reactions to what is happening but also to see the reactions of those around me.

The formation of the self is inextricably linked to Person – self-transcending, transcending free agency, “free in man” (as Viktor Frankl defined Person as the capacity to be self).

There is inevitably a conflict between Self and society, as the Self, on the one hand, requires self-detachment from others, and on the other hand, Self and society from each other. According to Alfried Längle’ existential-analytical theory of personality, two aspects are necessary to being oneself:

1. a self-determined attitude towards other people and the outside world;

2. sufficient clarity in dealing with oneself or, in other words, an adequate attitude towards oneself.

Both of these presuppose the following prerequisites:

– Perception of the self and delimitation of the self;

– Relating to the Self;

– Judgment of oneself.

In order to become self, one must see oneself and make a sufficiently clear and comprehensible image of the self. The latter is possible if there is some distance concerning one’s own feelings, actions and decisions, as if one has to take two steps back to see the complete picture of oneself in the mirror. For this distance to emerge, an encounter with another person is necessary, as if a symbolic point of reference for exploring the differences between “Own” and another and, consequently, finding one’s “Own”. If the person subsequently accepts the “own” found and, through this, also begins to respect the “own” of the other, a real encounter with the other takes place. In this way, it becomes possible for a person to be himself/herself freely in the field of the other person who is different from himself/herself. Self-establishment, therefore, means the possibility of being oneself with a sense of inner acceptance and permission to be oneself, despite one’s differences from the other. There is no need to hide and conceal one’s thoughts and feelings from others; one is not ashamed of one’s thoughts, ideals and actions – one is free to be oneself. Furthermore, this is possible when, with all the fidelity to oneself (the inner pole), you also respect others, allowing them to be themselves (the outer pole) to others through the ‘reflection’ you have given yourself. Thanks to this, you have managed to find your ‘Own’.

Based on the above, the dynamic structure of the Person is concurrently related to two poles, the external and the internal (Figure 1).

One part of a Person is entirely situated in the intimacy of his inner world, and the other part of the publicity of being – seen by others and dependent on others. Thus, the existential task of the Person in this double relationship is the need to find their own worth, to ground it internally, through attention and sensitivity to itself, to its feelings, and also to reinforce and affirm it externally through communication with others. In order to realise this difficult task, both the help and communication of others and the ability, the skill to draw a boundary between oneself and others, are necessary. A person can become genuinely fertile in their individuality and worth by striking a balance between these two extremes.

Thus, Self-establishment, according to Längle, is the formation of the Self, through which one acquires the ability to experience oneself as a Person, which constitutes the basis of self-worth and is one of the main objectives of life for the individual.

As part of this study, we have also reviewed previous empirical research on self-worth, which has demonstrated that most of the work in this area is focused on self-esteem (as a related concept, which we have already discussed above) and is predominantly implemented in a quantitative design. Usually, these are “classical” psychological studies with large samples and precise statistical analysis, allowing the identification of general trends and patterns, where self-esteem is investigated in correlation with various sociodemographic and psychological indicators. Such studies use standardised and validated methods, some of which are more or less concerned with studying self-worth. Studies such as these include the CSWS (the contingencies of self-worth scale), based on the hypothetical seven-factor model of Jennifer Crocker et al. (Crocker et al., 2003), which we have already mentioned. The scale measures self-worth as a phenomenon identical to self-esteem understood in the spirit of William James’ classical ideas of its relationship to life values. The authors suggest that successful and unsuccessful events in domains of contingent self-worth increase or decrease a person’s immediate sense of self-worth relative to his or her typical characteristic level. Moreover, these fluctuations in self-worth, depending on the nature of contingencies, have motivational consequences for the individual (Crocker, Wolfe, 2001).

Because of the link between self-worth and achievement, we view this approach and methodology more as exploring self-esteem than the sense of unconditional self-worth considered by humanistic psychotherapists. Nevertheless, in the context of empirical research on self-worth (as a concept of “self-worth”), the Crocker et al. questionnaire has frequently been used as a research methodology. The CSWS consists of 35 items, five for each of the seven value domains described in their proposed CSW (the contingencies of self-worth) model. Since its inception, the scale has been widely distributed (1158 citations in Google Scholar as of early 2020), has been adopted across seven cultures (Self and Social Motivation Lab, 2015) and has demonstrated good psychometric properties in several earlier empirical studies (Crocker & Luhtanen, 2003; Crocker et al., 2003; Luhtanen & Crocker, 2005). The most recent research on this topic at the time of writing is the work of Enrico Perinelli et al. (2022), who devoted a comprehensive analysis of the psychometric properties of the contingencies of the self-worth scale (CSWS). Two studies (Perinelli et al., 2022) provided the most comprehensive assessment of the psychometric properties of the CSWS in terms of structural validity and external correlates.

The CSW model was developed based on the assumption that feelings of self-worth are based on a set of valued intrapersonal and interpersonal actions (Crocker et al., 2003; Crocker, Wolfe, 2001). The authors of the model selected seven significant domains divided into two types or two groups (Crocker, Wolfe, 2001):

The former refers to the intrapersonal realm, which includes the realm of ‘virtue’ and ‘God’s love’. According to the authors, most people base their sense of worth on the conformity of their behaviour with a moral code (Solomon et al., 1991), which is why ‘virtue’ is positioned as one of seven spheres whose nature of experience influences a person’s self-value. In turn, the realm of ‘God’s love’ reflects the high value of a person’s belief that they are loved and unique in the eyes of God. This can positively impact one’s sense of self-worth, especially in religious people (Blaine & Crocker, 1995).

The second group of significant domains affecting self-worth are in the interpersonal domain, including academic competence, competition, approval from others, appearance and family support. The area of competence, and specifically academic competence, was chosen by the authors because many previous studies (e.g., Coopersmith, 1967; Demo, Parker, 1987; Richman et al., 1987; Rosenberg et al., 1995) have found that academic performance is related to overall self-esteem (as we noted, self-esteem and self-value are used synonymously in this model). The authors link the domain of competition to self-worth because people can base their attitudes about themselves on being competent and better than others (Josephs, Markus, & Tafarodi, 1992). The area of approval from others is considered because several studies (e.g. Cooley, 1902; Coopersmith, 1967; Shrauger, Schoeneman, 1979; Wylie, 1979) show the high importance to people of what others think of them. Attachment, relationships with significant others and family support are also vital to a person’s self-esteem and relationship with themselves. Therefore, they are one of the seven domains of influence on self-value in the CSW model (Harter 1986, cited in Perinelli et al., 2022). Finally, the model includes the appearance domain because it is one of the strongest predictors of global self-esteem and self-concept, especially in young people (Harter, 1986, cited in Perinelli et al., 2022).

The described approaches allow us to explore and describe certain factors that influence the formation of self-worth and the patterns of its change. However, the studies need to answer the questions about the content of self-worth as an autonomous concept, not identical to self-esteem, its essence and manifestations.

What characterises a person’s sense of self-worth? How does the individual experience it? What manifestations can we observe in ourselves and others?

The lack of research-based answers to these questions increases the relevance of the phenomenological study of self-worth conducted in 2022 by Darja Katz under the supervision of Jevgenija Karlin at the Baltic Institute of Psychotherapy. In addition to the theoretical review of materials on the topic, the study included a phenomenological analysis, including a specially designed questionnaire and further factor analysis to examine adults’ understanding of self-worth and to reveal three aspects of the phenomenon: affective (through which feelings self-worth is manifested, which emotional experiences are accompanied), cognitive (in which beliefs, thoughts and ideas it manifests) and behavioural (in which actions, behavioural manifestations).

Research method:

The research was carried out in a mixed design (qualitative-quantitative) and comprised six main stages:

1) The first stage involved a theoretical analysis of the literature and a review of previous research on self-worth, allowing the direction of the empirical study and its methods to be determined;

2) The second stage was a focus group with students and teachers from the Gestalt program at the Baltic Institute of Psychotherapy. The focus group aimed to clarify the understanding of the self-worth phenomenon, to determine the methodology and questions for further research;

3) In the third stage, an author’s self-worth research questionnaire was developed, consisting of six open-ended questions, namely:

1. Please continue the phrase: self-worth is…

2. How do you feel when you feel valued (‘self-worth’)?

3. When you feel valued, what do you think about yourself? What kind of person are you?

4. What actions do you take when you feel worthwhile?

5. How do you understand/feel that the other person feels valued? What are the other person’s manifestations of worth?

6. Please give an association or metaphor for the word self-worth. Write the first words or images that come to your mind.

The questions mentioned above were formulated in line with the aim of the study and its objectives: adults’ understanding of the phenomenon (question 1), exploring different aspects of the phenomenon, its affective (question 2), cognitive (question 3) and behavioural (question 4) manifestations. Also, for a more detailed understanding of the phenomenon, respondents were asked to describe how they see the manifestations of self-worth in others (question 5) and provide a metaphor for self-worth (question 6).

4) In the fourth stage, a questionnaire survey was conducted among 60 respondents. Participants in the survey: Russian-speaking Latvians, men and women aged between 23-57. The average age of the respondents was 35 years. The group of respondents included 25% men and 74% women. Eighty-nine per cent of respondents had higher education, and 11% had secondary education.

5) The fifth step was to analyse the data using multilevel factor analysis.

6) In the conclusion, a discussion of the obtained data and conclusions were made

The results of the research and their discussion:

The data obtained from the questionnaire was compiled into initial tables and further processed using factor analysis. The answers of the research participants were broken down into semantic units (as individual manifestations) and, on the contrary, were further combined into main categories. Factor analysis allowed a comprehensive study of the phenomenon of self-worth, highlighting its structure and manifestations at the three levels described above (affective, cognitive and behavioural) and revealing the manifestation and development of self-worth in the dynamics of development.

Thus, the content of the concept of “self-worth” was revealed in the course of the study. The analysis of the respondents’ answers to the continuation of the phrase “Self-worth is…” allowed us to identify 92 primary definitions reflecting different slices of the phenomenon of self-value. In further analysis of the data obtained, all the available phenomena were combined into 11 main categories (Table 1):

Table 1.

Generalised answers to the question “self-worth is …”

| Category | % |

| Self-acceptance | 14 |

| Self-respect | 10 |

| Feeling “I am” (right to be) | 10 |

| Love for oneself | 8 |

| Feeling of harmony | 8 |

| Self-focus | 5 |

| The ability to be useful | 5 |

| Self-confidence | 5 |

| Self-understanding | 4 |

| The feeling of inner strength | 3 |

| Autonomy | 2 |

| Other (single answers) | 5 |

| Phenomenon not disclosed | 21 |

As can be seen from the table, the majority of responses were attributed to the category “Self-acceptance” (14 %), followed by the categories – “Self-esteem” and “Feeling of self” (10 %), followed by the categories “Self-love” and “Feeling of harmony” (8 %), the categories “Self-focus”, “Ability to be useful” and “Self-confidence” were attributed to 5 % of responses. The category “Self-understanding” accounted for 4% of answers, “a feeling of inner strength” for 3%, and “Autonomy” for 2%. There were also isolated answers describing self-value: “The ability to create”, “Pride in oneself”, “A mature attitude towards oneself”, and “The way one follows one’s life principles”. 21% of the answers were tautological, not revealing the meaning, in the spirit of “Self-worth is the value of the self”.

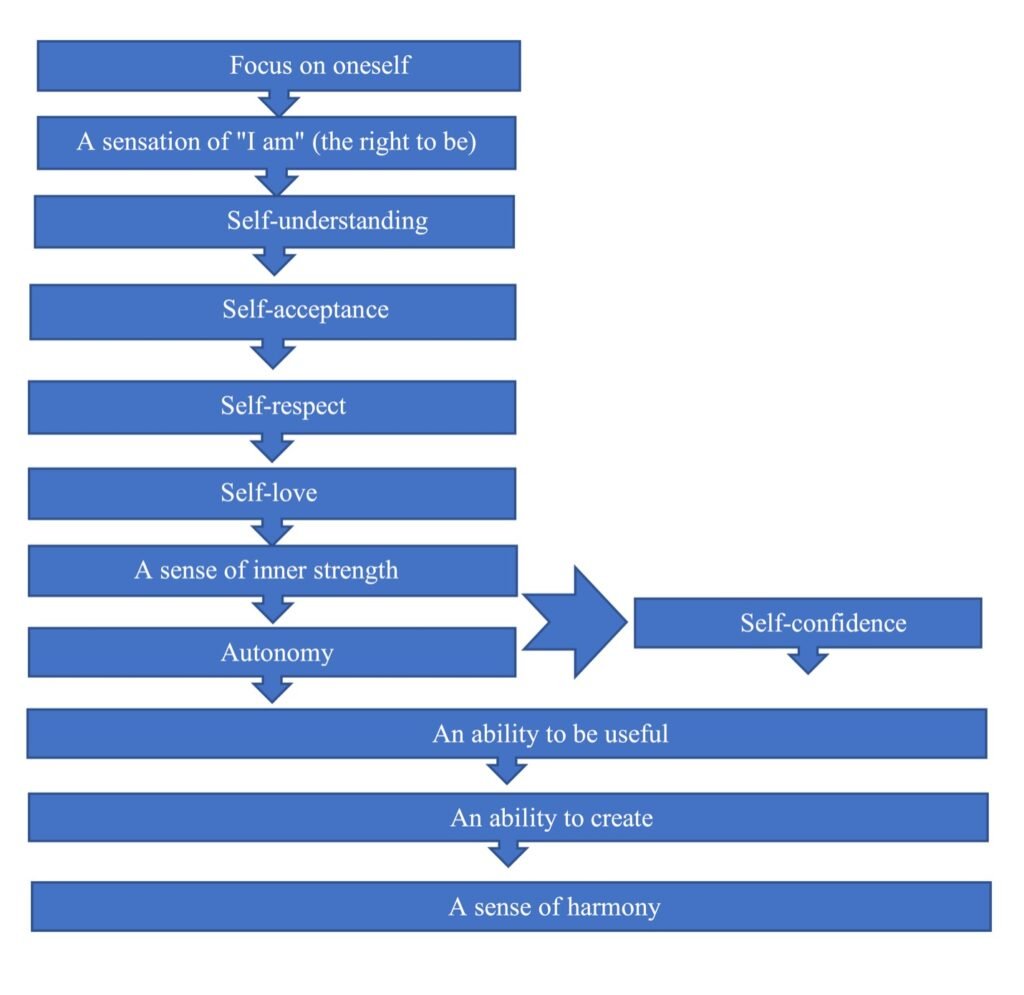

Analysing the results of the study of the meaning that respondents put into the concept of self-value (the questionnaire item “Please continue the phrase – self-worth is …”), a remarkable fact was that the categories obtained could be arranged in a particular sequence, revealing the phenomenon in its dynamics. Thus, by arranging the different aspects of self-value in terms of their relation to each other, highlighting the primary and the subsequent ones, we can see the sequence of appearance of each of the aspects in the process of formation of self-value of a person (Fig. 2).

Thus, we can observe the development of self-worth as a phenomenon in its dynamics. The primary and fundamental aspect is the focus of the individual on oneself, essentially self-awareness. (“Focus on oneself” – the ability to switch from the surrounding world, notice, and truly see oneself). Fundamental self-awareness enables the emergence of the following aspect – the sensation of “I am” (the right to be). By giving oneself the right to be, affirming one’s existence in this world, allowing oneself to sense, and recognising one’s feelings and needs, the next aspect of self-worth gradually becomes apparent – self-understanding, followed by peculiar habituation to what I am, with all the pros and cons, self-acceptance appears. After self-acceptance, self-respect and self-love become possible. Where love has emerged, there is also a sense of inner strength (the desire to share with others, subcategories of the conducted factor analysis). With the presence of inner strength, autonomy is possible, which in turn jointly forms self-confidence. When an individual has all of the above, there is also the ability to be useful and the ability to create, which ultimately leads to a sense of harmony.

The resulting sequence agrees with the ideas of Alfried Längle (2002, 2005), who believes that self-worth is a balance between two opposing poles: the person’s presence in their inner world and being with others, upon which there is the possibility of allowing oneself to be oneself, despite differences from others. So, what is the similarity of A? Längle’s ideas with the empirically derived categories of this study? In my opinion, the first categories are shown in Figure 1 – “Focus on oneself”, “Sense of I am (the right to be)”, “Self-understanding”, “Self-acceptance” “Self-respect”, “Self-love” – this is the person’s intimacy with their inner world, according to A. Längle. Then, with the development of the following categories, “Sense of inner strength”, “Autonomy”, and “Self-confidence”, the focus of the individual begins to shift towards the outside world. Finally, with the emergence of the “Ability to be useful”, and “Ability to create”, the focus is even more outwardly directed.

Thus, I get the impression that the resulting sequence of phenomena to the first question of this work, “What is self-worth”, are some intermediate stages between the two poles of the continuum: “Inner focus of the individual” and “External focus of the individual” (Fig. 3).

This developed sequence of factors describing the phenomenon of self-worth can potentially be applied in psychotherapeutic practice, serving as a schema or map to guide the journey of discovering the client’s self-worth. Analyzing the responses to the survey’s second question, we can observe the spectrum of emotions that individuals experience when they perceive their own worth. The primary emotions expressed include confidence, tranquillity, harmony, energy surge, happiness, joy, satisfaction, pride, responsibility, and gratitude. Additionally, specific intentions or inclinations towards action were revealed among the responses, such as an energy surge, a desire to do something and bodily sensations of warmth.

Examining the results of the question: “When you feel valuable, what do you think about yourself? Who are you?” the most commonly encountered descriptions were: “I am good, I am cool, I can handle anything, I can accomplish anything, an energy surge, and a desire to take action.” These answers align with the responses to the previous question. The main difference lies in the prominence of self-satisfaction, which encompasses responses such as “I am good,” “I am cool,” and “Satisfaction with oneself and one’s achievements” (see Appendix 4). In these answers, we observe a positive self-approval evaluation that individuals grant themselves. Here, it can be presumed that self-worth is a personal perception of oneself, independent of external circumstances, depending on the individual’s personal relationship with oneself. This is reminiscent of the unconditional love and sense of unconditional worthiness we longed for from our parents during childhood. Furthermore, regarding the desire to do something and the desire to share when one has an abundance or even excess, it indicates the presence of resources to give.

The responses to the following question, which delves deeper into the actions individuals desire to take when they experience self-worth, further reveal the recurring phenomenon of an energy surge and the desire to act. Nearly half of the responses – 39.5% – focused on actions individuals wanted to perform for others, affirming the notion that when one feels valuable, the desire and ability to share arise. This ability involves noticing others, and transitioning from an internal focus to an external one. Furthermore, 11.8% of the responses mentioned the desire to try something new, which can also be attributed to exploring the external world according to Person Theory by Alfred Längle (2005). Additionally, 9.2% of the responses stated that individuals, when feeling their own worth, engage in the same actions as in other periods of their lives but with a different mood. For example, “The same actions as usual, but with greater confidence,” “I do not know exactly what actions, but I perform tasks with more joy,” or “Actions that leave no room for doubt, done wholeheartedly.” Here, the sense of confidence and joy, previously mentioned in responses to the first and second questions, is again evident. Another type of action mentioned in 7.9% of the cases was “Hearing oneself, savouring the moment,” which aligns with the feelings of tranquillity and self-love.

Among the responses to the fifth question of the survey, which asks how individuals perceive someone else’s sense of worth and its manifestations, the following categories were identified: self-assurance, tranquillity, openness to the world, satisfaction with oneself and one’s life, personal boundaries, kindness and love towards others, ease of communication, the ability for free self-expression, and the ability to evoke respect, among others. All these manifestations (or those similar in meaning) have already been mentioned in responses to previous questions. In turn, particular attention should be given to the manifestation that emerged for the first time among the responses – namely, “an inflated sense of self.” According to Alfred Längle, an inflated sense of self is also a compensatory mechanism that arises when self-worth is partially or entirely absent. It represents a facade – an artificial sense of self-worth that masks its absence, which others may occasionally interpret as genuine self-worth, but in reality, it is not.

In the last section of the survey, participants were asked to provide associations/metaphors for the term “self-worth” and write the first words or images that came to mind. Among the responses, recurring images included precious gems, light, trees, flight, wings, the sea, and parents. Each of these images evokes specific emotions and characteristics associated with individuals. A precious gem signifies value, significance, and uniqueness. The light image aligns with the sensation of warmth previously mentioned in responses. Flight and wings may represent feelings of lightness and freedom, while the sea symbolizes strength and simultaneous tenderness/care. The image of parents may also be linked to the idea that they were the individuals from whom we could receive our self-worth through acceptance and unconditional love. However, despite the variety of images described by respondents, they accounted for only 26.4% of the total number of responses. The remaining 62.1% described emotions and states, such as love, confidence, harmony, pride, resourcefulness, tranquillity, respect, self-sufficiency, self-realization, and others.

It can be noted that despite the difference in all the questions in the questionnaire described earlier, the answers received largely overlap with each other and can also be built into the sequence shown in Figure 2. as feelings and actions accompanying each of the stages on the path to self-esteem. For example, self-sufficiency can be attributed to autonomy, feelings of love to the stage of “Self-love”, feelings of respect to “Self-esteem”, etc. Thus, we can see the coherence of the identified factors with each other and the integrity of the phenomenon of self-worth.

Conclusions

Factor analysis has allowed us to comprehensively study the phenomenon of self-worth, highlighting its structure and manifestations on three levels (affective, cognitive and behavioural) and revealing the display and development of self-worth in dynamics.

The research allowed for the identification of basic categories that elucidate the phenomenon of self-worth. The following “elements” or components of self-worth were determined: self-focus, the sense of “I am” (the right to exist), self-understanding, self-acceptance, self-respect, self-love, the sense of inner strength, autonomy, self-confidence, the ability to be helpful, the ability to create, and the sense of harmony.

The listed factors were correlated with each other, forming a sequence describing the dynamics of the formation and manifestation of self-worth.

In the humanistic approach, working with the topic of human self-worth, we intuitively sense these elements; however, this topic is empirically researched for the first time, and a clear structure is presented for the first time, which can be valuable (self-valuable) in the practical work of psychotherapists.

The conducted phenomenological analysis allows us to conclude that self-worth is a person’s attitude towards themselves, independent of their achievements or the opinions of others, and is a balance between two opposing poles: the presence of the individual in their inner world and being with others, upon which, there is the possibility to allow oneself to be oneself, despite differences from others (as, in particular, Professor Alfried Längle writes in his works).

Primary categories of self-worth, such as a focus on oneself, the sensation of “I am” (the right to be), self-understanding, self-acceptance, self-respect, and self-love, reflect the intimacy with one’s inner world (using Längle’s concepts). The development of following categories, such as the sensation of inner strength, autonomy, and self-confidence, reflects the shift of the individual’s focus towards the outside world, which then reaches its maximum in this vector through such manifestations as the ability to be useful and the ability to create.

Based on the identified factors describing the phenomenon of self-worth, a method for researching self-worth (as an autonomous concept, not identical to self-esteem) may be developed in the future, allowing for further research on this topic.

About the authors:

Jevgenija Karlin holds a doctorate in psychotherapy (PhD from SFU, Vienna, Austria) and is a practising psychologist, lecturer and supervisor of the training programme in the integrative approach at the Baltic Institute of Psychotherapy jevgenija@karlin.lv

Daria Katz is a Gestalt practitioner and a student in the Gestalt Psychotherapy Programme at the Baltic Institute of Psychotherapy

darja.kasjane@gmail.com

References:

Blaine, B., & Crocker, J. (1995). Religiousness, race, and psychological well-being: Exploring social psychological mediators. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(10), 1031–1041.

Burns R. B. (1982), Self-Concept Development and Education. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Education, 441 p.

Cooley, C. H. (1902). Human nature and the social order. New York: Scribner’s.

Coopersmith S., (1967), The Antecedents of Self-Esteem. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman & Co. – p.p. 283-326.

Crocker, J., Brook, A. T., Niiya, Y., & Villacorta, M. (2006). The pursuit of self-esteem: Contingencies of self-worth and self-regulation. Journal of Personality, 74(6), 1749–1772. https://doi.org/10.1111/ j.1467-6494.2006.00427.x

Crocker, J., & Luhtanen, R. K. (2003). Level of self-esteem and contin- gencies of self-worth: Unique effects on academic, social, and finan- cial problems in college students. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(6), 701–712. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0146167203029006003.

Crocker, J., Luhtanen, R. K., Cooper, M. L., & Bouvrette, A. (2003). Contingencies of self-worth in college students: Theory and mea- surement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(5), 894–908. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.894.

Crocker, J., Nuer, N. (2003) The Insatiable Quest for Self-Worth// An International Journal for the Advancement of Psychological Theory 2003, Vol. 14, No. 1

Crocker, J., & Wolfe, C. T. (2001). Contingencies of self-worth. Psychological Review, 108(3), 593–623. https://doi.org/10.1037/ 0033-295X.108.3.593.

Demo, D. H., & Parker, K. D. (1987). Academic achievement and self- esteem among black and white college students. Journal of Social Psychology, 127(4), 345–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545. 1987.9713714.

James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology (Vol. 1). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Josephs, R. A., Markus, H. R., & Tafarodi, R. W. (1992). Gender and self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(3), 391–402. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.391.

Luborsky, L., (1984) Principles of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy: A Manual for Supportive-expressive Treatment, New York, Basic Books.

Luhtanen, R. K., & Crocker, J. (2005). Alcohol use in college students: Effects of level of self-esteem, narcissism, and contingencies of self- worth. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 19(1), 99–103. https:// doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.99.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, and society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mruk C. (1999), SelfEsteem: Research, Theory, and Practice. 2nd ed. N. Y.: Springer. 240 p.

Perinelli E., Alessandri G., Vecchione, M., Mancini, D. (2022) A comprehensive analysis of the psychometric properties of the contingencies of self-worth scale (CSWS) Current Psychology (2022) 41:5307–5322

Richman, C. L., Brown, K. P., & Clark, M. (1987). Personality changes as a function of minimum competency test success or failure. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 12(1), 7–16. https://doi. org/10.1016/S0361-476X(87)80034-6.

Rogers, C. (1964) Toward a modern approach to values // J. of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1964. Vol.68(2), p. 160-167.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400876136.

Rosenberg, M., Schooler, C., Schoenbach, C., & Rosenberg, F. (1995). Global self-esteem and specific self-esteem: Different concepts, dif- ferent outcomes. American Sociological Review, 60(1), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096350.

Self and Social Motivation Lab. (2015). Contingencies of self-worth (CSW) scale. Found at http://faculty.psy.ohio-state.edu/crocker/ lab/csw.php#13 on May 26, 2018.

Shrauger, J. S., & Schoeneman, T. J. (1979). Symbolic interactionist view of self-concept: Through the looking glass darkly. Psychological Bulletin, 86(3), 549–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.86.3. 549.

Solomon, S., Greenberg, J., & Pyszczynski, T. (1991). A terror management theory of social behavior: The psychological functions of self- esteem and cultural worldviews. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 24, 93–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08) 60328-7.

Wylie R. C. (1974), The Self-concept. V 1: A Review of Methodological Consideration and Measuring Instrument. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, p. 57-116.

Wylie, R. C. (1979). The self-concept: Theory and research on selected topics (Vol. 2, 2nd ed.). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Langle, A. (2005), Person, Existential Analytical Theory of Personality, Genesis Publishers

Langle, A. (2002), Grandiose Solitude, Year, Moscow Psychotherapeutic Journal, no. 2

Mlodik, I. (2017) The Bottom of the Endless Well or the Painful Way of the Narcissist’ // E-article on the B17 Portal. – https://www.b17.ru/blog/67915/ [accessed 20/09/2022].

Orlov, A. B. (2002) The human-centred approach in psychology, psychotherapy, education and politics (on the 100th anniversary of C. Rogers) // Voprosy psychologii, 2002, 2, 64-84.

Fromm, E. (2022) To have or to be? – MOSCOW: AST. – 320 с.

Footnotes

1. published on the personal page of the website https://www.drchristinahibbert.com/self-esteem-vs-self-worth/ [access date: 02/10/2022]

Cite this article as:

Katz, D., & Karlin, J. (2023). Research on the Phenomenon of Self-Worth in the Psychotherapeutic Context. Journal of Integrative Psychotherapy and Systemic Analysis. https://psychotherapy-journal.com/research-on-the-phenomenon-of-self-worth-in-the-psychotherapeutic-context/