An Overview of Narcissism

The concept of narcissism, rooted in the early psychoanalytic theories, has evolved significantly over time, warranting a more nuanced understanding of its dual aspects – healthy and negative.

In the following sections, this essay will further elaborate on the distinction between healthy and destructive narcissism, using the theoretical foundations laid by Kernberg and Kohut and subsequently examining these concepts through the lens of existential perspective.

Early philosophical views have greatly influenced current interpretations of narcissism, typically seen negatively in both everyday and clinical contexts. Freud (1914) posited that narcissism, a normal sexual development stage, is innate and necessary developmental stage for all individuals, characterizing it as the self-focused state of the libido from birth.

Kernberg (1975) defines healthy narcissism and abundant object love as a consequence of good inner-object relations. That is a normal healthy narcissism, built on maintaining self-esteem and the ability to enjoy life. A self-concept and well-integrated internalisations of Others support this function. An integrated world and affective memories of people who love us support our sense of self-worth and allow us to feel the love of others in the present.

Kohut (1971) emphasised the role of empathy in psychological development and proposed that narcissistic needs could transform into more mature forms, leading to solid self-respect, while narcissism is an independent form of motivation or energy, not just libido redirected towards oneself.

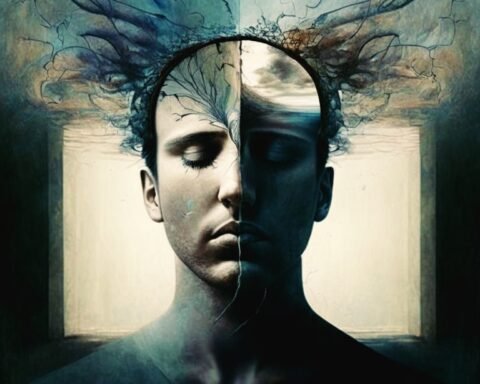

On the other hand, unhealthy narcissism becomes severe and constant, it can escalate to Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD). Despite varying clinical intensities, NPD typically presents grandiosity, jealousy conflicts, ethical disregard, inner emptiness, a sense of brokenness, and is often linked to violence, aggression, and borderline personality disorders.

Kernberg (1975) sees people developing pathological narcissism and bad object relations as a consequence of bad inner object relations. As introduced in Kohut’s self-psychology model, a lack of empathy from parents during a child’s development leads to narcissistic psychopathology (McLean J. 2007). That leads to a complete inability to develop control of their self-esteem. The narcissistic adult swings between an irrational overestimation of self and an irrational sense of inferiority, hence they become reliant on other people to determine their sense of value and self-worth.

From an existential perspective, narcissism is on a narrow line between normal self-esteem and unhealthy focus on the self. The individual is the creator of his meaning and purpose, a process imbued with freedom but also fraught with anxiety and uncertainty (Heidegger, 1962; May, 1953; Sartre, 2003). Healthy narcissism reflects this existential task, manifesting as a balanced self-importance that maintains respect for the world and others, even in the face of personal limitations (van Deurzen-Smith, 2000).

However, existential thought also highlights the pitfalls of narcissism.

As May (1953) observed, vanity and narcissism can undermine courage, as one relies on external admiration rather than personal conviction. This excessive self-focus can tip into unhealthy narcissism, reflecting an imbalance or neglect of life’s essential physical, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions, as we ignore given aspects of being- in-the-world.

The Positive Side: Healthy or Normal Narcissism

Initially, Freud (1914) suggested that personality can be more or less narcissistic. He proposed that healthy narcissism entails holding realistic views about oneself without diminishing the shared experiences with loved ones, a characteristic often found in negative narcissism. Freud asserted that narcissism is an inherent part of human nature, crucial for day-to-day functioning. While taken to the extreme, it hinders establishing relationships grounded in love and trust.

Moreover, his follower Federn (1929) was the first to introduce the notion of “healthy narcissism”, indicating that a narcissist is simply one who has an adequate level of self-love. His definition focused on self-love and being realistic and grounded in what a person can achieve.

However, the work of Kohut and Kernberg has made the concept of healthy or normal narcissism perhaps more customary.

Kohut (1971) believed every child has “normal narcissism.” If these narcissistic essentials are satisfactorily met, the person progresses to a more adult type of self-confidence instead of being stuck at a lower level of personality development.

He argued that a child fantasises about a grandiose self and ideal parents. A belief in their flawlessness and the perfection of everything they are part of is harboured by every individual. As one grows up, grandiosity gives way to self-esteem, and the idealisation of parents becomes the basis of core values.

Consequently, “normal narcissism” reflects an individual’s healthy self-love. Kohut proposed that this was necessary for creativity, empathy, and fulfilment. It is apparent that understanding and accepting oneself fully with self-confidence, and self-esteem can be considered expressions of healthy narcissism. It is both protective and helps us adapt to new people and situations.

Equally important are the ideas of Kernberg (1975), who posits that normal adult narcissism is defined as a normal adaptive mode of self-regulation. It depends on a healthy structure of the Self, is associated with self-image stability and constancy of internal images, is characterised by the capacity for stable and enduring interpersonal relationships and involves an integrated Super Ego that enables instinctive needs to be met.

Furthermore, the first precondition for normal narcissism is an integrated sense of Self. In contrast to a split or disorganised concept of Self, this integrated Self provides a sense of certainty and capacity for internal well-being and safety. Thus, an integrated self-concept is essential for the normal regulation of self-esteem.

Moreover, our internal world of significant others bolsters normal self-esteem (and, therefore, normal narcissism). We internalise the images of those close to us, creating an internal world that supports our representation of the Self.

Besides, when normal infantile narcissism transitions into adulthood, it can turn into narcissistic personality disorder. This transition to a pathological state sets the stage for our discussion on unhealthy narcissism in the following section.

The Narcissistic Shadow: An Exploration of Unhealthy Narcissism

According to Kohut (1971) Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) can begin to manifest anywhere from the late oral stage and continue to develop throughout various stages, even extending into the latency phase of development. He claims that adult narcissistic psychopathology is a result of parental lack of empathy during development. If a child is denied the rewarding experience of feeling appreciated through reflective validation, the exaggerated sense of self-importance can persist pathologically into adulthood (Ornstein PH, Kay J., 1990).

Hence, failing to provide appropriate empathic feedback during critical times in a child’s development, the child does not develop the ability to regulate self-esteem, and so the adult vacillates between an irrational overestimation of the self and feelings of inferiority. Additionally, narcissistic individuals are prone to experiencing emptiness and depression in response to narcissistic injury (Kohut, 1971).

Throughout their lives, individuals with narcissistic personalities will resort to one of these two primitive patterns to maintain their unstable self-image. When the grandiose self is activated, these individuals will seek others who continuously reflect their inflated self-worth. Conversely, when the idealised parent image is triggered, they strive to merge with an all-powerful entity that they idealise.

Kernberg, on the other hand, takes a different perspective. His view, grounded in object relations theory, highlights the significant role of aggression and conflict in the psychological evolution of narcissism, with a focus on the individual’s hostile feelings and envy towards others. Within this “conflict model”, the emergence of narcissistic tendencies is explained by early experiences with unresponsive, emotionally distant or hostile childhood caretakers (Kernberg, 1984).

In response, the child cultivates a sense of uniqueness as a refuge from such harsh reality. This sense of uniqueness is gradually transformed into an unhealthy, inflated self-perception that serves as a shield against the child’s anger arising from his or her inability to incorporate positive object relations. Pathologically narcissistic individuals rely heavily on rudimentary defence mechanisms such as idealisation, devaluation and cleavage, while the capacity for feelings of sadness, remorse and grief remains underdeveloped. Consequently, shame, envy, and aggression often dominate their immediate emotional reactions. Kernberg (1975) holds that the narcissistic individual as a child was left emotionally hungry by a chronically cold, unempathetic mother.

In addition, unhealthy narcissists, characterised by an inflated self-image, crave admiration and attention. When this external validation stops, they experience anxiety and boredom. These individuals idolize those who feed their narcissism, devalue others, and harbour envy indiscriminately. Their relationships are manipulative, assuming “special rights”, and their emotions are shallow, often appearing cold and ruthless. They may display dependent traits, needing affection and admiration, but their inability to trust and tendency to devalue others hinder true dependence.

Kernberg (1975) pinpoints that explicit narcissism is not just a fixation on early development and a simple deviation in the development of object love. However, it is characterised by the simultaneous development of pathological forms of self-love and pathological forms of object love.

While the psychodynamic approach offers valuable insights into the development and manifestation of different forms of narcissism, in the next section, we will use an existential lens to explore this concept holistically, encompassing intrapsychic dynamics and the existential state of the individual.

Narcissism Through an Existential Lens

The existential approach offers a unique perspective on narcissism, suggesting that humans are not just meaning-seeking but also meaning-making creatures. This is the point of departure for a more profound exploration of narcissism from an existential perspective.

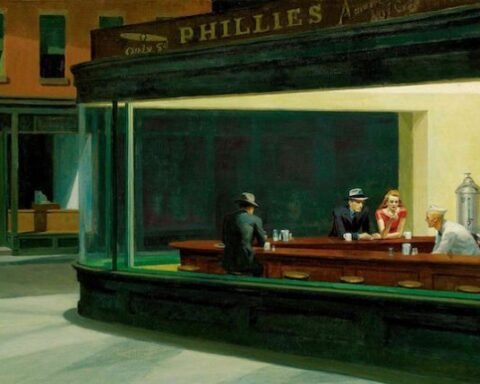

Frankl (1984) posited that the central driving force in life is the “will to meaning,” suggesting that individuals constantly seek significance and purpose. Individuals with pronounced narcissistic traits often experience boredom (Emmons, 1981), hinting at a potential failure to find purpose, leading to an ‘existential vacuum’, which can further lead to existential frustration and the experience of emptiness and meaninglessness when one’s desire for significance is unfulfilled.

Yalom (1980) extends this view, suggesting that humans, inherently meaning-making creatures, are also driven by the fear of non-being and the awareness of their mortality. This aligns with Shaw’s (2000) perspective that narcissism is a motivational construct developed to counter the existential dread of personal insignificance. In this view, narcissism is a personal myth system that shields individuals from confronting their mortality and personal limitations.

An existential standpoint on narcissism would consider Heidegger’s (1962) concept of “Being-in-the-world,” which suggests that our existence is not isolated but fundamentally interconnected with others and our environment. Therefore, an excessive focus on oneself, as seen in narcissism, could be interpreted as a denial or distortion of this fundamental interconnection, leading to an inauthentic existence.

Moreover, van Deurzen-Smith (2000) suggests that narcissism is inherently ingrained in our biology, psychology, socialisation, culture, and spiritual life. However, an awareness of the needs of our world can balance this self-centeredness, suggesting that a degree of narcissism could be healthy and adaptive. As a motivational structure, narcissism can manifest in a positive, meaning-creating form, a negative, meaning-obscuring form, or any variant. Regardless of the individual’s style, it will inevitably influence their functioning within life’s physical, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions.

Contrasting with the psychoanalytical approach, which emphasises early developmental experiences, the existential perspective focuses on the individual’s present lived experience and engagement with inherent existential realities. This perspective sees healthy narcissism as a quest for authenticity, freedom, and personal responsibility. In contrast, negative narcissism is construed as an attempt to escape existential anxieties, marking a departure from authenticity.

Nevertheless, while providing an exceptional viewpoint, the existential perspective on narcissism still needs to be well-established and needs empirical scrutiny. Furthermore, while it enriches our understanding of narcissism by adding a philosophical depth, it is essential to approach these theories as complementary to other perspectives and continue seeking empirical validation.

Conclusion

In summary, when approached from both psychoanalytic and existential standpoints, the study of narcissism uncovers a complex matrix of self-views, relational dynamics, and the individual quest for significance. Guided by the theoretical frameworks of Kohut and Kernberg, this essay has examined narcissism as a continuum, extending from healthy self-appreciation to detrimental self-absorption.

Healthy narcissism, manifested by equilibrium in self-esteem and good self-regulation, performs an adaptive function. Conversely, negative narcissism, distinguished by an exaggerated self-image, fluctuating self-regard and relational issues, often originates from early life experiences and a deficit of empathic reinforcement.

The essential evidence underscoring this position comes from the exploration of Kohut’s emphasis on the role of empathy in healthy narcissistic development and Kernberg’s focus on the impact of aggression and conflict in negative narcissism. Both theorists accentuate the critical role of early childhood experiences and parental influences in shaping an individual’s narcissistic tendencies.

As we look forward, it is essential to consider these insights in the broader scope of understanding and treating narcissistic personality disorders. Embracing an empathetic and understanding approach, as suggested by Kohut, while also acknowledging the potential for internal conflict and aggression, as proposed by Kernberg, could lead to more effective therapeutic strategies.

The existential lens further illuminates our understanding by recognising the individual’s quest for meaning and managing existential anxieties. This juxtaposition of perspectives underscores the importance of a multi-dimensional approach to understanding narcissism that can inform more effective therapeutic interventions.

About author

Max Karlin is a practising psychologist and trainee existential therapist at the New School of Psychotherapy and Counselling (NSPC – Existential Academy) and Middlesex University, London. With a professional journey spanning over two decades in commerce and industry, Max brings a wealth of diverse experiences to his practice. Beyond his private practice, he helps leaders and specialists from various sectors to navigate their daily lives, goal-setting, decision-making, conflict resolution, and meaning-making in the face of anxiety, uncertainties and high-pressure situations. He is passionate about researching how psychotherapy can contribute to social change and foster a better world. A founder and co-editor of the Journal of Integrative Psychotherapy and Systemic Analysis.

References

Emmons, R. A. (1987). Narcissism: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 11-17.

Federn P. (1929). On the Distinction Between Healthy and Pathological Narcissism. Reprinted in P. Feder, Ego psychology and the psychosis. London: Maresfield Reprints, pp. 323-364.

Frankl, V. E. (1984). Man’s search for meaning. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Freud, S. (1914). On narcissism: An introduction. Standard Edition (Vol. 14, pp. 69–102). London: Hogarth Press

Heidegger, M., Macquarrie, J., & Edward Schouten Robinson. (1962). Being and time. Harper And Row.

Kernberg, O. (1975). Borderline conditions and pathological narcissism. New York, NY: Jason Aronson.

Kernberg, O.F., (1984) Severe Personality Disorders: Psychotherapeutic Strategies. Yale University, New Haven.

Kohut, H. (1971). The analysis of the self. New York, NY: International Universities Press.

May, R. (1953). Man’s search for himself. New York: Norton.

McLean J. (2007). Psychotherapy with a Narcissistic Patient Using Kohut’s Self Psychology Model. Psychiatry (Edgmont (Pa. : Township)), 4(10), 40–47.

Ornstein PH, Kay J. Development of psychoanalytic self psychology: A historical-conceptual overview. In: Tasman A, Goldfinger SM, Kaufmann CA, editors. Review of Psychiatry. American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 303–22.

Sartre, J.-P. (2003). Being and nothingness (H. E. Barnes, Trans.; 2nd ed.). Routledge.

Shaw J. A. (2000). Narcissism as a motivational structure: the problem of personal significance. Psychiatry, 63(3), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.2000.11024914

van Deurzen-Smith, E. (2000). Everyday mysteries: Existential dimensions of psychotherapy. New York: Routledge

Yalom, I., (1980). Existential psychotherapy. New York, NY: Basic books.